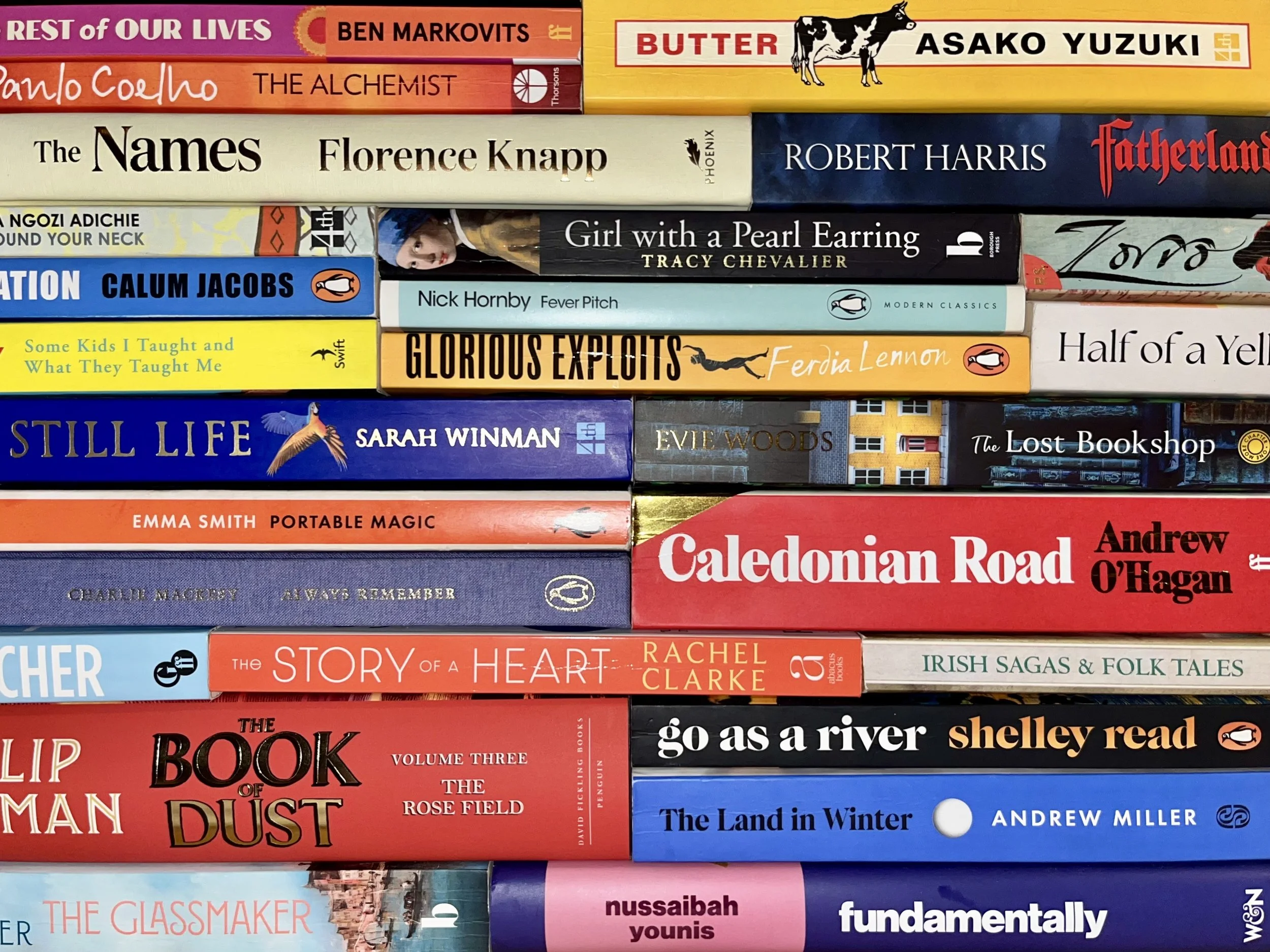

Every book I read in 2025

From prizewinners and modern classics to non-fiction accounts, retellings and short-story collections, here is a round-up of the books I have adored, abhorred, enjoyed or endured this year, admittedly excluding all those I have reread, either on audiobook (principally Middlemarch, Persuasion and His Dark Materials) or with my students (Macbeth, A Christmas Carol and so on)!

1) The Lost Bookshop by Evie Woods ★★★★

Blending historical drama with magical realism, The Lost Bookshop’s standout feature has to be Woods’ enchanting descriptions of the bookshop itself and its humorous way of nudging characters in the right direction. It managed to be both charming and intriguing, dipping into romance, academia, religion and Irish history.

2) Go as a River by Shelley Read ★★★

This was the first book I discussed with my book club and it falls firmly into the category of “you love it until you talk to someone else about it and realise it’s nowhere near as good as you thought it was!”. Whilst I enjoyed Read’s lush descriptions of natural landscapes, the different narrative perspectives and the themes of female solidarity and resilience, the novel is underpinned by an unrealistic romance, which fails to resonate. Nevertheless, the idea of “going as a river” (going with the flow, whilst also gathering and carrying all your experiences with you) did strike a chord and has stuck with me.

3) Zorro by Isabel Allende ★★★

Allende’s swashbuckling Bildungsroman explores the origin of the masked hero and ticks off everything you would expect: explosive duels, dramatic escapes, dashing heroics, romance and crusades against injustice. It was interesting and expansive historically, detailing the impact of Spanish colonialism on the Indigenous people of the United States and the role of the French Revolution in shaping other European countries in the 1700s. Although Allende perhaps attempts to mitigate the absence of the female perspective within this genre by placing a quill into the hand of one of Zorro’s lifelong friends, Isabel de Romeu, from whose perspective the story is told, I found her voice to be quite grating: ironic, given all her asides about what makes a powerful narrative! Nonetheless, Zorro was exciting and I raced through it with ease.

4) The Only Woman in the Room by Marie Benedict ★★★

This book was absolutely fascinating from a historical perspective, exploring the life of Hedy Kiesler, a Jewish Hollywood star, who fled Austria prior to WW2 and became involved in various efforts to support the Allies in their fight against Nazi Germany. Although the writing was hilariously overdone in places, particularly Hedy’s internal monologue, the narrative was so interesting that it (almost) didn’t matter!

5) The Thing Around Your Neck by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie ★★★★★

I am not usually drawn to short stories, but this collection is nothing short of masterful; filled with interesting or unique narrative choices (from stories written in the second-person to intrusive, ominously-knowing narrators), Adichie’s tales are bursting with intensity: she manages to pack so much in, yet you are still left wanting more. As with much of Adichie’s longer-form fiction, The Thing Around Your Neck is a clever investigation of race, gender and class, particularly considering the experience of the Nigerian diaspora. Even as each story ends bleakly, Adichie invites you to feel a flicker of hope. Absolutely gorgeous.

6) The Alchemist by Paul Coelho ★★

When I left school, I was given this as a present, along with the promise that it would guide me in determining my future path. Many years later, I have only just got round to reading it and I must say I was underwhelmed. Coelho uses the tale of a young shepherd, who gives up his flock to hunt for an elusive treasure, to exemplify his message that everything in life is connected and that we need to listen to the world around us for guidance and truth. At times, it felt overly moralistic and more like a fable or a parable than a novel. I’m not sure it will shape my future very significantly at all!

7) Glorious Exploits by Ferdia Lennon ★★★★

Set in 412 BC following the failed Athenian invasion of the Sicilian city of Syracuse, Glorious Exploits follows Gelon and Lampo: two rudderless, unemployed Syracusan men. Seemingly inspired by Plutarch’s Life of Nicias, which makes fleeting reference to Athenian prisoners being fed or even freed from slavery if they could recite some Euripides, Lennon takes this even further and eventually has his protagonists stage a Greek tragedy that is acted by the Athenians in the very quarry in which they are imprisoned. Through a hilarious vernacular narrative voice, Lennon blends tragic conventions with a sense of hope in the power of art and story. This is definitely a book that I hope to reread in 2026.

8) Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie ★★★

I was really excited to read Half of a Yellow Sun, but I must say I didn’t enjoy it half as much as I was expecting to. Whilst it was eye-opening from a historical perspective (I didn’t even know there had been a war between Nigeria and the secessionist state of Biafra in the 1960s), the novel felt emotionally flat to me in comparison to Adichie’s punchy short stories.

9) Butter by Asako Yuzuki ★

How did this book win Waterstones Book of the Year? As literally anyone I even so much as saw whilst reading it will already know, I found Butter to be utterly unbearable. From the lack of crime-related tension to the unnervingly sexual descriptions of food and the bizarre relationships between almost all the characters, I found this to be a very tough read.

10) Fundamentally by Nussaibah Younis ★★★

Through her plucky yet thus-far unlucky protagonist, Younis’ debut novel explores the fascinating landscape of the deradicalisation and repatriation of ISIS brides. Whilst I felt that a few of the events were unbelievable and some of the supporting characters were rather thinly-drawn, this was nonetheless an enjoyable read, emphasising the way in which social and political forces can influence individuals’ faith and families.

11) A New Formation by Calum Jacobs ★★★★

A New Formation is a fascinating collection on the role of Black British footballers in shaping the modern game. From Raheem Sterling’s brave exposure of biased media coverage to the difficulties of observing Ramadan during the season, the mentorship that "Uncle Ian" Wright gives younger Black footballers and the experiences of Hope Powell as England’s first Black national team coach, I learnt so much about both football and British society across the last few decades. I was particularly interested by the thread which ran throughout the book about the pressure placed on Black people to do the work of anti-racism. Eloquent and emotive, A New Formation really changed my perspective on the role and power of sport across society.

12) Fever Pitch by Nick Hornby ★★★★★

If you are an Arsenal fan and you haven’t read Fever Pitch, buy it now. If you are a football fan and you haven’t read Fever Pitch, buy it now. If you couldn’t care less whether anyone in the world ever kicks a football again and you haven’t read Fever Pitch, buy it now. What is ostensibly an autobiographical book detailing Hornby’s love affair with Arsenal is really a thoughtful, painful, witty expression of life’s oscillations. Organised by football match rather than chapter, Hornby uses the lens of sport to reflect on his childhood, relationships, jobs and dreams. Hilarious, heart-warming and honest, I would honestly recommend this to anyone: football fan or not!

13) Still Life by Sarah Winman ★★★★★

I cannot overstate how much I adore this book. It is perfect. Forget Butter, this is my Book of the Year. Have a read of the article on my worst book hangovers here, if you need further persuading.

14) The Names by Florence Knapp ★★★★

The Names was another book club book and this one really divided opinion. The premise of the novel is that it follows the three potential lives of a baby boy as he grows into adulthood, depending on the name his mother chooses to give him (Julian, as she wanted, Bear, as her older daughter wanted, or Gordon, as her husband wanted). What the blurb fails to mention though is that the mother is the victim of horrific domestic abuse and therefore what follows becomes more of an investigation of the ripple effects of abusive relationships and less of a question of the extent to which your name determines the shape of your life. Despite being difficult and uncomfortable at times, I did find it to be a thought-provoking read.

15) Fatherland by Robert Harris ★★★

I love a Robert Harris and this was another pacy thriller, set in 1964 and exploring an alternative history in which Germany had won WW2. It initially reads as a classic detective novel yet the book comes to centre on exposing a cover-up of the existence of concentration camps. It definitely made me think about the way in which atrocities can be denied, diminished or even forgotten about in our modern world.

16) Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me by Kate Clanchy ★★★★

What a beautiful book! An absolute love letter to teaching and poetry. Honest and powerful, Clanchy gives voice to the difficulties she experienced being a white middle-class woman teaching students of predominantly different socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds to herself. Since reading it, I found out that she received criticism for some aspects of the book, which I was initially surprised by, until I realised that I had bought the newly-edited version, which had altered some of her problematic phrasing. I still think she was brave to put all her potential misconceptions and struggles with perspective into words. The book draws attention to the political nature of people’s beliefs about school and education, as well as giving some amazing ideas and structures for poetry clubs or enrichment activities.

17) The Story of a Heart by Rachel Clarke ★★★★

Throughout The Story of a Heart, Clarke, herself a doctor, weaves the history of organ transplantation and its associated medical advances with the astonishing story of children Max, who was waiting for a heart transplant, and Keira, whose family donated her organs following a tragic road traffic accident. Sympathetically and lyrically written, The Story of a Heart is full of stunning and brave individuals, from the families of the central children to the brilliant medical professionals who were involved in their care. Clarke also details Max and his family’s efforts to change the process of organ donation to an opt-out system in order to increase the number of donors, leading to the Organ Donation (Deemed Consent) Act 2020, known as Max and Keira's Law. Both educational and heart-warming, this is a must-read.

18) The Wedding People by Alison Espach ★

In my notes, I have just the phrase “instant hatred”, which I think encompasses my feelings about The Wedding People. The novel deals flippantly with themes of suicide and I felt uncomfortable about its theatricalisation of mental illness. Although it gained some more narrative drive as it went on, this is certainly not a book I would recommend.

19) The Year of the Runaways by Sunjeev Sahota ★★

I really wanted to like The Year of the Runaways, but I found it to be very slow and difficult to get into. Detailing the experiences of a series of young men from India living illegally in the north of England, whilst shifting back to their upbringings, I felt that there were too many different characters and timelines for any of their narratives to gain any real emotional depth. Many of the novel’s episodes felt disjointed or disconnected; I kept turning the page to find a conversation or interaction had unexpectedly finished, without any sense of conclusion. The ending felt like a discordant attempt at hope, given the unrelentingly bleak storylines, and although I did learn much about the Indian caste system and the way these prejudices continue to predominate within Indian communities in Britain, I found it difficult to get excited about this book.

20) The Glassmaker by Tracy Chevalier ★★★★

Initially set on the island of Murano in the 1400s, The Glassmaker begins by following Orsola Rosso, daughter of a prominent glassmaker. However, this narrative is complicated by what Chevalier calls “time alla Venezia”, using a metaphor of a skimming stone skipping across the water to explain how she moves her characters forward through different time periods, right up until the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020. Whilst this was initially intriguing, I found it difficult to pinpoint the purpose behind this choice, perhaps attempting to draw attention to how much (or how little?) had changed. The most interesting development was perhaps an economic one, as tourism and mass production significantly alter the Rosso family’s trade, arguably cheapening their craft. Chevalier’s descriptions of the process of glassblowing and beadwork were fascinating; I found myself desperately wanting one of the little glass dolphins that Antonio, Orsola’s love-interest, was so fond of making. Despite my reservations regarding the novel’s central conceit and my frustration with Orsola’s lack of character progression across the centuries, I did really enjoy this book and the romantic, fantastical impression of Venice has stayed with me.

21) The Secret Teacher by Anonymous ★★★

I flew through The Secret Teacher: an account of an anonymous man’s first few years in the classroom. Funny and relatable, it is packed with hilarious incidents in school, as well as heart-warming moments with students. However, aspects of it didn’t quite ring true for me; it felt like the kind of book that someone who has struggled through teacher training thinks they need to write. I think I probably would have enjoyed it more if I wasn’t a teacher myself, although of course everyone’s schools and experiences are different.

22) The Safekeep by Yael Van Der Wouden ★★★★

This book was not at all what I was expecting it to be; halfway through I was thinking why on earth was I recommended this, but I promise it has a twist worth waiting for! Set in post-WW2 Netherlands, The Safekeep is a thrilling consideration of home, family and the legacy of conflict. Winner of the Women’s Prize for Fiction this year and shortlisted for the Booker Prize last year, it is certainly worth a read.

23) Girl with a Pearl Earring by Tracy Chevalier ★★★★

Needing a break from Caledonian Road but inspired by its protagonist’s love of Vermeer, I turned back to Tracy Chevalier. Girl with a Pearl Earring tells the simple, evocative tale of Griet, Vermeer’s servant, who eventually inspires and sits for his striking and iconic painting. As in The Glassmaker, Chevalier invests in exploring the details of artists’ crafts and I enjoyed her illustration of the process of painting: setting up still-life scenes, making paints and mixing colours. It was a predictable turn of events, but expressed in an enchanting way.

24) Caledonian Road by Andrew O’Hagan ★

Caledonian Road is an attempt at a state-of-the-nation satire, reminiscent of Victorian classics like Vanity Fair; however, without the incisive narration that era was so good at, many of the characters were reduced to frustrating caricatures, voicing contrived views. Whilst there were pockets of real horror and emotion, on the whole Caledonian Road felt like a 657-page experiment in how to make drama and scandal boring.

25) Pompeii by Robert Harris ★★★★

Set in the days running up to the eruption of Vesuvius, Pompeii captures both the ingenuity and corruption of the Roman world. Harris often chooses an unusual perspective from which to explore a well-known moment in history and Pompeii is no exception; its protagonist is an aqueduct engineer, racing to make repairs as pre-eruption tremors disturb the network of aqueducts running across the Italian countryside. With an excellent band of supporting characters, from the vindictive overseer, Corax, to the heroic love interest, Corelia, the opportunistic and ambitious former slave, Ampliatus, and the scholar and commander, Pliny the Elder, this was very entertaining; I tore through it in less than a day, but it was still nowhere near as good as Harris’ Cicero trilogy in my view!

26) Irish Sagas & Folk Tales by Eileen O’Faoláin ★★★

Although I wouldn’t usually be tempted by fairy or folk stories, I bought this in a second-hand bookshop whilst on holiday in Galway. Convincingly told in a medieval style by a modern author, it felt very fitting to be reading these classic Irish tales in a classic Irish pub!

27) The Secret Commonwealth by Philip Pullman ★★★

I was so excited to read The Secret Commonwealth, but I think it falls into the category of “the tricky second album”; the whole text feels like it’s simply building up to the final book of the trilogy. The novel sees Lyra, Pan and a host of other characters travelling independently across Europe, with various sub-plots, and thus its scope becomes almost too broad to maintain strong narrative coherence. Although it was an entertaining enough thriller, it lacked the subtlety, depth and magic that I have come to associate with Pullman and I am not ashamed to admit that I much prefer Lyra as a fearless child than an adrift young adult.

28) Always Remember by Charlie Mackesy ★★★★★

As pure and perfect as The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse, Always Remember continues the tale of Mackesy’s previous book with even more warmth, humour and evocative illustrations. I very much relate to the mole’s obsession with cake and I know that Always Remember will be the book that I reach for when I need to find some peace. It is just wonderful. See my thoughts on The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse here.

29) The Rest of Our Lives by Benjamin Markovits ★★★

Shortlisted for the Booker Prize, The Rest of Our Lives is pitched as a road-trip narrative; having dropped his youngest child off at university, a father drives across America, finally leaving his unfaithful wife, as he had vowed to do years before. It’s a very lonely novel; not only are we cut off from accessing Tom’s perspective due to his frustratingly self-censored narration (he repeatedly says “oh I don’t need to tell you about that”), he himself also appears unable to access his emotional reality, rendering this text sad in a rather distant way. Markovits does pose interesting questions regarding who we are able to open up to and why, but on the whole I found this novel very empty.

30) The Land in Winter by Andrew Miller ★★★★

The Land in Winter depicts the relationships between a series of couples in a small village during the “Big Freeze”. Set in 1962, Miller subtly exhibits the way in which the seismic events of WW2 continued to pervade the consciousness of all the characters, whilst also looking ahead to the future. I particularly enjoyed Miller’s depiction of Rita’s struggles with her mental health; I thought his personification of her internal anxieties was really effective. Whilst I struggled with aspects of Miller’s writing style (chapters often ended with some incomprehensible yet grim imagery and moments were excessively melodramatic), I did enjoy the way the different narratives blended together, confusing you regarding whose household you were in. The ending was achingly sad and strange and I thought the book was altogether quite affecting, although it’s difficult to put my finger on exactly why.

31) Portable Magic by Emma Smith ★★★★

Subtitled “A History of Books and their Readers”, I was expecting Portable Magic to be centred on the transportive power of literature, exploring how books can carry us to historical, fantastical or futuristic places. Portable Magic is not that book; instead, it’s a deeply-researched investigation of the book as a material object, focusing on the physical form of the book itself rather than its content. Smith’s intellect comes through on every page, yet she writes in such an engaging and accessible manner; there is no academic snobbery here. From Armed Services Editions revolutionising paperback printing post-WW2 to repulped Mills & Boon romances being used to build the M6 Toll Road, Portable Magic is filled with enchanting and unexpected facts about the roles that books play in all of our lives, without necessarily even reading them. Whilst I did read Portable Magic cover to cover, you could certainly dip in and just read the chapters that were of particular interest to you: censorship, propaganda, book burning, bibles, printing, artwork, gifts, collecting, trade and beyond. This was a fascinating read and fittingly a very satisfying edition too.

32) The Rose Field by Philip Pullman ★★★

I was nervous about reading The Rose Field, the conclusion to Philip Pullman’s second trilogy set in Lyra’s world. It continues where The Secret Commonwealth left off, with Lyra and Pan still separated and travelling across Europe and the Middle East, both looking for each other and continuing their individual quests. Although it would be impossible to top the conclusion of The Amber Spyglass, I have to admit I was disappointed by The Rose Field’s ending; perhaps I should have welcomed its less satisfying and more “grown-up” resolution, but in reality all it’s done is prompt me to begin rereading the His Dark Materials trilogy once again in order to assure myself of its perfection!

33) Queen Macbeth by Val McDermid ★★★

Having taught Shakespeare’s Macbeth quite a few times now, it was refreshing to read McDermid’s version of the Scottish royals, painting an entirely new vision of Lady (or Queen) Macbeth. Downplaying her transgressive, ambitious behaviour, McDermid focuses on the romance and violence that precipitated her and Macbeth’s apparently stable and successful reign. Despite some slight inconsistencies, I found this to be a clever, interesting book and I enjoyed spotting all the direct quotations that she had used from Shakespeare’s play!

From the frustrations of Butter and Caledonian Road to the absolute joys of Still Life, The Thing Around Your Neck and Fever Pitch, 2025 has been full of literary interest. My family often comment that they hear far more about the books that I hate than the ones I love and in that sense even they have given me enjoyment through the excuse to have a good rant! In 2026, I am looking forward to reading even more historical fiction, as well as some non-fiction, as this year has taught me it can be just as emotional and engaging as a novel can.